I was one of the few folks in Washington D.C. bouncing back from the holidays eager for the year to start. I was eager to get back because I was about to meet with this winter’s Common Bond participants.

Common Bond

Common Bond was born out of Tuesday’s Children, an organization started to support the kids who lost a parent in 9-11. The organization grew and folks found a way to expand it to meet the needs of young people all around the world who have lost a parent to terrorism. Now they have a summer camp held at Bryn Mawr College. Young people come together, often from “opposing” sides of a conflict, discuss their losses and how to move forward.

Common Bond meets Conflict Resolution

A group of twenty 18-25-year-olds from this program came to the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University because they want to prevent cycles of violence.

This special group not only wants to thrive in spite of their tragic losses, they want to contribute to the world around them.

4 Day Crash Course on Conflict Resolution

My colleagues and I (Alex Cromwell, Nawal Rajeh, Leslie Dwyer, and Joseph Green) taught them conflict resolution basics as well as how to use theatre and poetry to work through issues of loss and oppression.

It was a whirlwind. (What’s great about working with 18-25 year-olds is that they can stay up until 4am talking to each other and show up in the morning ready to roll! I don’t think I was ever able to do that…it’s incredible.)

Responding to Mass Atrocity

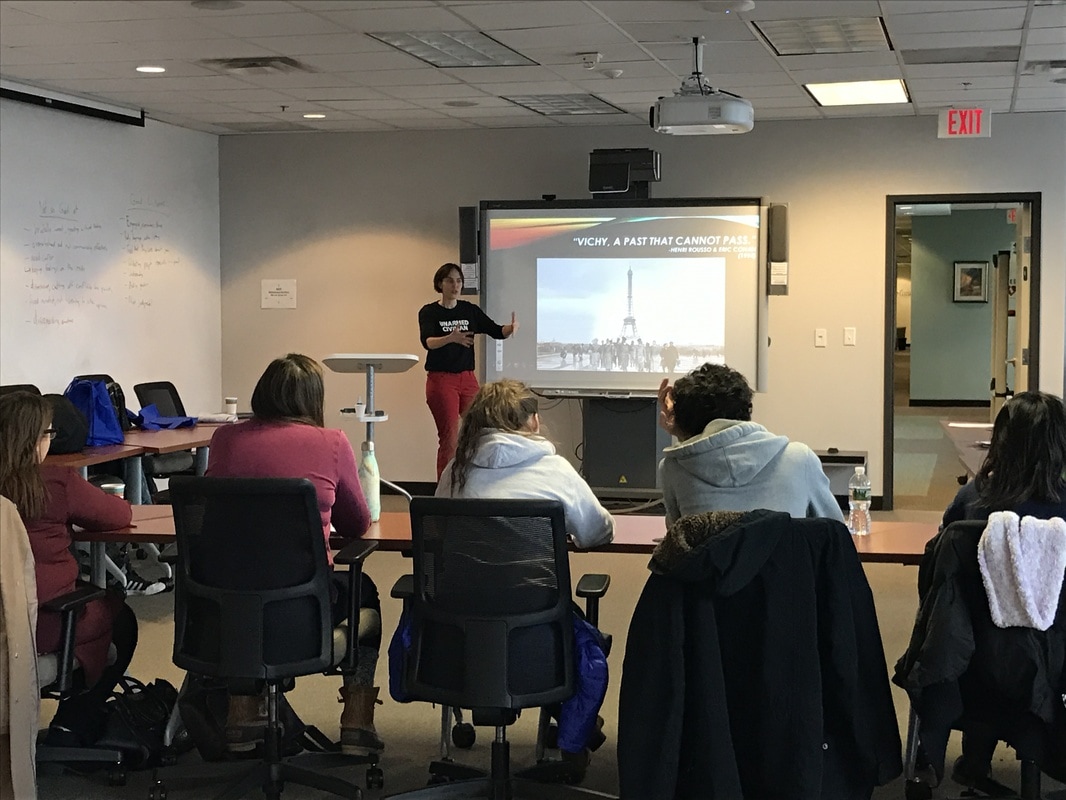

Having never lost a parent to terrorism or lived in a conflict zone, it seemed in appropriate to tell them about loss. So, I shared with them what I learned spending thousands of hours with 80 Holocaust survivors during my doctoral research.

Today’s survivors almost all were children during World War II, meaning many lost their parents around the same age. They also had a great deal in common with our students from Haiti, Palestine, Sri Lanka who are living in active conflict zones.

I shared with the Common Bond participants firstly, that I know 90-year-olds still struggling with the murder of their parents. This issues last and affect them differently over the many decades of their long lives.

I also shared with them the myriad of ways Holocaust survivors have responded. Luckily, they had just spent a day at the museum so had an idea of the scope and nature of the atrocity.

From my research on the multi-decade French National Railways (SNCF) conflict (about a train company who transported Jews towards death camps and still exists today), I learned that survivors varied in their social and political responses.

Transitional Justice

The public responses to mass violence and atrocity are often addressed under the title of ‘transitional justice.’ This includes issues of financial compensation, apologies, commemoration, transparency (the opening of archives), trials (lawsuits) and truth commissions.

We talked about how certain political events can make any of these more or less difficult. In the case of the Holocaust, the fall of the Berlin Wall, created the space for much discussion about events of World War II. The Cold War had effectively frozen discussions. In their cases, many still live under corrupt regimes, so archives, apologies, compensation, etc. will likely not come for many years.

Those from Ireland explained that certain archives have been locked for 100 years – effectively making sure they only open when everyone responsible has died, all the victims, as well as all of their children.

We talked about how new information will likely surface throughout their lives creating new opportunities to participate in lawsuits, commemorative spaces, etc. One participant who lost a parent in 9-11, for example, says she has just joined the lawsuit against Saudi Arabia. She talked about her mixed feelings about this.

Holocaust survivors I interviewed also had mixed feelings about lawsuits, even when they participated. The seminar gave us time to start to talk about these complicated feelings.

Not Everyone Wants to Fight

I also shared stories from people who did not want to fight, they chose to share their stories with high school students, write memoirs, help people currently fleeing persecution. There are many ways to contribute.

I warned them that they might feel pressure to respond in certain ways. Holocaust survivors sometimes pressured and judged one another about how their counterparts responded or did not.

Hierarchies of Suffering

Survivor groups are far from homogenous. There are pressures and there are judgements. There are also, I discovered, hierarchies of suffering. For example, some believe only those who went to the death camps really suffered whereas others claim being a hidden child was no picnic either. Many hidden children were physically or sexually abused. Others I met nearly starved to death.

As Brigittine French observes, “not all participants enter into the contest over memory as equals; some actors have lost more than others.”[1]

I shared this as a way to preempt repetition of this hierarchy within their group. There is no need to compare suffering and loss. The issue, of course, comes when financial compensation is involved. How much is your father worth? Why are some people paid for their losses and others are not? Who decides?

It ultimately just is not fair. Someone who lost a parent to violence in Haiti will simply not receive nearly the compensation and support of someone who lost a parent in 9-11.

In spite of these tremendous differences, these young people came together and supported one another.

I am starting 2017 with such a tremendous optimism. The masters’ students I met this fall teaching at SciencesPo Lille in France as well as at the University of Malta were all astonishing, eager, intelligent and ready to make their contribution.

Much light still shines…made even more apparent by a dark room.

…We’re all in this together…

[1] French BM (2012) The Semiotics of Collective Memories. Annual Review of Anthropology 41, no. 1: 343.